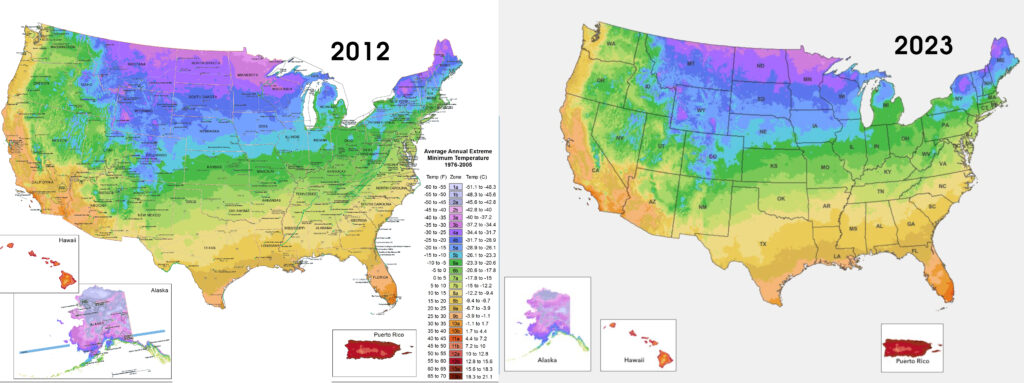

Perhaps you’ve seen the new USDA hardiness zone map that came out this week? For the first time in eleven years, we have an updated map, and about half of the United States moved half a zone warmer (with the rest staying in the same zone they were in before). You can check your new zone here.

Before you rush out and buy tropical trees to plant in your garden, though, I thought I’d share a few thoughts from our last fifteen-plus years growing fruit.

Averages aren’t everything

First, you need to understand what the zone map really means. It’s a thirty-year average of annual extreme low temperatures in your location.

First, you need to understand what the zone map really means. It’s a thirty-year average of annual extreme low temperatures in your location.

In other words, that’s the coldest it’s likely to get in your garden on an average year — so sometimes the temperature will never drop that low and sometimes you’ll see a freak cold spell that dips even lower. In fact, as the climate changes, unusual cold waves (and heat waves) are becoming more common, so my biggest piece of advice is this:

Be conservative when picking out those fruit trees! Maybe don’t choose a fig that’s only on the edge of hardy where you’re located. Instead, if you live in zone 6b (as we now do), it’s smarter to select varieties hardy to at least zone 6a. This is especially true for fruit plants that take several years to mature.

Frost pockets

While you’re planning smart, be sure to consider microclimates. Even though the area we moved from is technically half a zone warmer than the one we’re in now (meaning we moved from zone 6b to zone 6a…which is now zone 6b!), our hilltop tends to evade early and late freezes that would have definitely struck our previous deep-valley pocket.

While you’re planning smart, be sure to consider microclimates. Even though the area we moved from is technically half a zone warmer than the one we’re in now (meaning we moved from zone 6b to zone 6a…which is now zone 6b!), our hilltop tends to evade early and late freezes that would have definitely struck our previous deep-valley pocket.

So no matter what the map claims, believe your eyes if they say you’re actually half a zone colder or warmer than your neighbors. And consider late freezes prone to result in fruitless years when selecting varieties — late bloomers can be a major plus.

Heat and drought

Finally, it’s worth looking at the flip side of the coin. The hardiness zone maps don’t say anything about annual high temperatures or droughts, but for many of us both of those climate concerns are increasingly relevant in our gardens.

Finally, it’s worth looking at the flip side of the coin. The hardiness zone maps don’t say anything about annual high temperatures or droughts, but for many of us both of those climate concerns are increasingly relevant in our gardens.

For example, despite drip irrigation, our hilltop gets so bone dry during scorching summers that I keep losing shallow-rooted blueberry plants. I intend to move the survivors to a wetter location (which I’ll tell you about in a later post). For now, just remember that there’s a lot more to keeping fruit plants happy than making sure they evade the worst winter ice.

Shameless plug

If you want to read more of my thoughts on choosing fruit plants that will produce with minimal headache on your part, definitely check out my Weekend Homesteader: Winter ebook (or nab the full series in paperback form).

And I’d love to hear from you. How are you changing your gardening plans in response to the new maps?